Using Excel, plot a scatter plot of concentration vs. Absorbance using the date from the parallel and serial dilutions on the same graph. Add a best fit line and get the y = mx + b equation for each and the R value. Do the data points from both dilution series that were prepared seem to fit a straight line? Serial dilutions are often performed in steps of 10 or 100. They are described as ratios of the initial and final concentrations. For example, a 1:10 dilution is a mixture of one part of a solution and nine parts fresh solvent. For a 1:100 dilution, one part of the solution is mixed with 99 parts new solvent.

Introduction

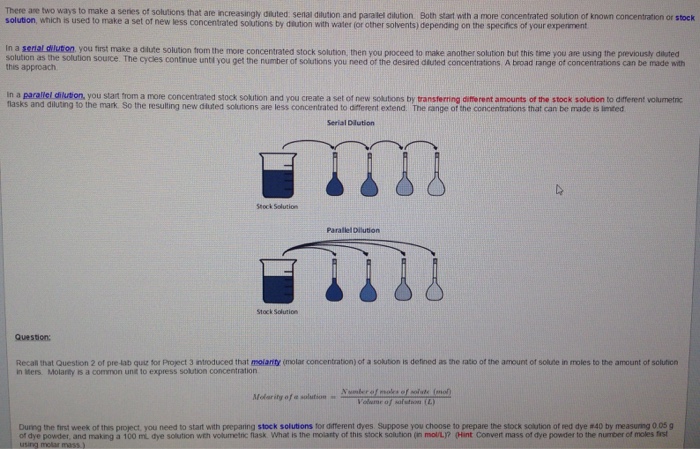

A Serial dilution is a series of dilutions, with the dilution factor staying the same for each step. The concentration factor is the initial volume divided by the final solution volume. The dilution factor is the inverse of the concentration factor. For example, if you take 1 part of a sample and add 9 parts of water (solvent), then you have made a 1:10 dilution; this has a concentration of 1/10th (0.1) of the original and a dilution factor of 10. These dilutions are often used to determine the approximate concentration of an enzyme (or molecule) to be quantified in an assay. Serial dilutions allow for small aliquots to be diluted instead of wasting large quantities of materials, are cost-effective, and are easy to prepare.

The dilutions cover the range from 1/2 to 1/100 unevenly. In fact, the 1/2 vs. 1/3 dilutions differ by only 1.5-fold in concentration, while the 1/10 vs. 1/100 dilutions differ by ten-fold. If you are going to measure results for four dilutions, it is a waste of time and materials to make two of them almost the same. When do I use the serial dilution technique instead of the parallel dilution technique? Another way to make dilutions is to use some of your existing stock solution to make a dilute solution, then use some of the dilute solution to make an even more dilute solution, then use some of that solution to make an even more dilute solution, and so on.

Equation 1.

[concentration factor= frac{volume_{initial}}{volume_{final}}nonumber]

[dilution factor= frac{1}{concentration factor}nonumber]

Key considerations when making solutions:

- Make sure to always research the precautions to use when working with specific chemicals.

- Be sure you are using the right form of the chemical for the calculations. Some chemicals come as hydrates, meaning that those compounds contain chemically bound water. Others come as “anhydrous” which means that there is no bound water. Be sure to pay attention to which one you are using. For example, anhydrous CaCl2has a MW of 111.0 g, while the dehydrate form, CaCl2 ● 2 H2O has a MW of 147.0 grams (110.0 g + the weight of two waters, 18.0 grams each).

- Always use a graduate cylinder to measure out the amount of water for a solution, use the smallest size of graduated cylinder that will accommodate the entire solution. For example, if you need to make 50 mL of a solution, it is preferable to use a 50 mL graduate cylinder, but a 100 mL cylinder can be used if necessary.

- If using a magnetic stir bar, be sure that it is clean. Do not handle the magnetic stir bar with your bare hands. You may want to wash the stir bar with dishwashing detergent, followed by a complete rinse in deionized water to ensure that the stir bar is clean.

- For a 500 mL solution, start by dissolving the solids in about 400 mL deionized water (usually about 75% of the final volume) in a beaker that has a magnetic stir bar. Then transfer the solution to a 500 mL graduated cylinder and bring the volume to 500 mL

- The term “bring to volume” (btv) or “quantity sufficient” (qs) means adding water to a solution you are preparing until it reaches the desired total volume

- If you need to pH the solution, do so BEFORE you bring up the volume to the final volume. If the pH of the solution is lower than the desired pH, then a strong base (often NaOH) is added to raise the pH. If the pH is above the desired pH, then a strong acid (often HCl) is added to lower the pH. If your pH is very far from the desired pH, use higher molarity acids or base. Conversely, if you are close to the desired pH, use low molarity acids or bases (like 0.5M HCl). A demonstration will be shown in class for how to use and calibrate the pH meter.

- Label the bottle with the solution with the following information:

- Your initials

- The name of the solution (include concentrations)

- The date of preparation

- Storage temperature (if you know)

- Label hazards (if there are any)

Parallel Dilution Formula

Lab Math: Making Percent Solutions

Equation 2.

Formula for weight percent (w/v):

[ dfrac{text{Mass of solute (g)}}{text{Volume of solution (mL)}} times 100 nonumber ]

Example

Serial Dilution Vs Parallel Dilution

Make 500 mL of a 5% (w/v) sucrose solution, given dry sucrose.

Serial Vs Parallel Dilution

- Write a fraction for the concentration [5:%: ( frac{w}{v} ): =: dfrac{5: g: sucrose}{100: mL: solution} nonumber]

- Set up a proportion [dfrac{5: g: sucrose}{100: mL: solution} :=: dfrac{?: g: sucrose}{500: mL: solution} nonumber]

- Solve for g sucrose [dfrac{5: g: sucrose}{100: mL: solution} : times : 500 : mL : solution : = : 25 : g : sucrose nonumber]

- Add 25-g dry NaCl into a 500 ml graduated cylinder with enough DI water to dissolve the NaCl, then transfer to a graduated cylinder and fill up to 500 mL total solution.

Comments are closed.